The Final Stellation of the 120-Cell, {5/2,3,3}

Introduction

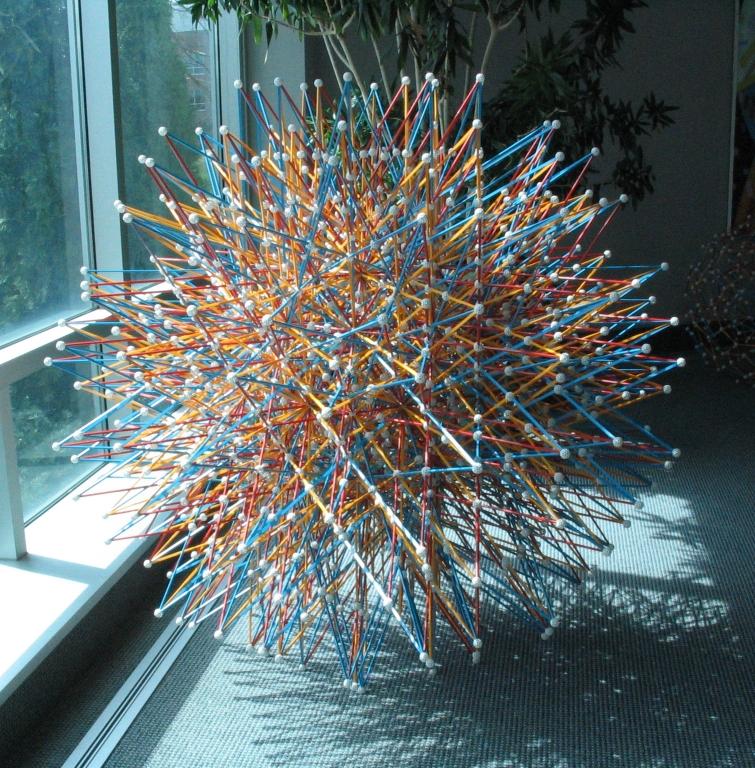

Here is a Zome model of the final stellation of the 120-cell. It was constructed by a group of about 40 people, mainly students, on Saturday March 24, 2007, at the Lee Honors College at Western Michigan University.

Some Math

If extended far enough, the edges of the "standard" convex 120-cell intersect at the vertices of this polytope. Hence this is an "edge stellation" of the 120-cell. This is the "final" stellation of the 120-cell because extending the edges any further does not result in a regular polytope. This polytope is also a 120-cell, but the cells are great stellated dodecahedra, arranged so that 4 edges meet at every vertex. One should also study the intermediate, first stellation of the 120-cell.

As it turns out, the vertices of the final stellation of the 120-cell coincide spatially with the vertices of a large convex 120-cell. In fact, combinatorially speaking, this polytope is not distinguishable from the standard 120-cell. One should compare this with the fact that the great stellated dodecahedron is combinatorially identical to the ordinary convex regular dodecahedron, while at the same time sharing the same vertices spatially. One should compare this with the fact that the regular pentagram is combinatorially identical to the ordinary convex regular pentagon, while at the same time sharing the same vertices spatially.

The ratio of the edge lengths of this polytope to those of the convex 120-cell sitting deep inside is b6, where b denotes the Golden Ratio, and the ratio of the edge lengths of this polytope to those of the first stellation also contained herein is b3. (Thanks to François Guéritaud for providing these ratios.)

The Construction

Aside from the planning, the construction had two main phases. First we constructed roughly a thousand small assemblies, each using one or two connectors and between 1 and 10 struts. Then we had to assemble all of these assemblies into the big spiky ball pictured above. This video, produced by a participant Paul Thompson, nicely shows the assembly of all these parts into a whole.

The construction, from the time when all parts were completely disassembled until the time the model became a single entity, took about 6 hours. This was about 3 times longer than anticipated. The first phase, that of making about a thousand small assemblies took about an hour and a half, while the second phase, that of assembling them into a whole, took much longer. The problem was that for a long time, the model was too small for more than a couple people to work on it simultaneously.

Conclusion

The existence of this model establishes the fact that it is possible to "Zome" all 16 regular polytopes in 4 dimensions. This is remarkable considering that this model weighs about 25 pounds. We are lucky that 12 balls touch the floor, so that each ball has only about 2 pounds of force to support. We are also lucky that the model is considerably less wobbly than its convex counterpart, the 120-cell, and so the weight distribution stays fairly constant.

This model remained on display in Rood Hall for until summer 2014 when it had to be dismantled.

Dedicated Zomers and their Achievement

Reference

H. S. M. Coxeter. Regular Polytopes. 3rd ed. Dover Publications Inc., New York, 1973.